It’s controversial candy season. Let’s do this.

If there’s two things I love it’s chocolate (milk) and smart, funny, kickass writing. In this great article from The Atlantic’s Megan Garber, we get both. Enjoy.

By Megan Garber

OCTOBER 27, 2016

I generally enjoy milk chocolate, for basic reasons of flavor and texture. For roughly the same reasons, I generally do not enjoy dark chocolate. *

Those are just my boring preferences, but preferences, really, won’t do: This is an age in which even the simplest element of taste will become a matter of partisanship and social-Darwinian hierarchy; in which all things must be argued and then ranked; in which even the word “basic” has come to suggest moral judgment. So IPAs are not just extra-hoppy beers, but also declarations of masculinity and “palatal machismo.” The colors you see in the dress are not the result of light playing upon the human eye, but rather of deep epistemological divides among the world’s many eye-owners. Cake versus pie, boxers versus briefs, pea guac versus actual guac, are hot dogs sandwiches … It is the best of times, it is the RAGING DUMPSTER FIRE of times.

But back to chocolate. These micro-debates lend themselves especially well to candy, it turns out, which is probably why, this spoooooky time of year, candy rankings join heated discussions of the latest predictably offensive Halloween costumes as seasonal Stuff to Talk About. (It’s controversial candy season, motherfuckers!) And so, cumulatively, 21 Kinds of Halloween Candy, Ranked and A Ranking Of 40 Halloween Candies From Nastiest To Raddest and the 52 Best and Worst Halloween Candies—Ranked and A Definitive List of the Best and Worst Halloween Candy, Ranked and their many other counterparts have combined to bestow judgment.

And the judgment, collectively, if I may sum it up, is that candy corn is disgusting and also weird-looking, and Mr. Goodbar is the superior selection in the Hershey’s Minis bag, and Mounds are proof that God loves us, and Raisinets are proof of the opposite, and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups are proof that even in these turbulent times it could turn out that committed monogamy makes a certain sense. Also: Nerds are warty nonsense; Whoppers are okay but why are their coatings so shiny; Butterfingers are delicious but also possibly Illuminati-left clues about impending apocalypse; the best M&M color is red and the blue ones are trying too hard and the oranges are trying not hard enough and let’s not even start on the green; Rolos are fine; Milk Duds are unacceptable; Smarties are good in an “actually…” kind of way; Twix are what they are, but—wait for it—also demand the plural verb; Snickers are, obviously, at the very tippy-top of the Halloween hierarchy, but only if they’re Fun-Sized, and if someone puts a regular-sized version into your bag, that person is most likely either over-compensating for something or trying to murder you with the tiny razor blade that has been lodged between the peanuts and the nougat, and it probably goes without saying but while we’re on the subject of Snickers, any candy that bills itself as Bite-Sized can GTFO, which means Go to Functional Overload, and if you have a different interpretation then you can go functional-overload yourself.

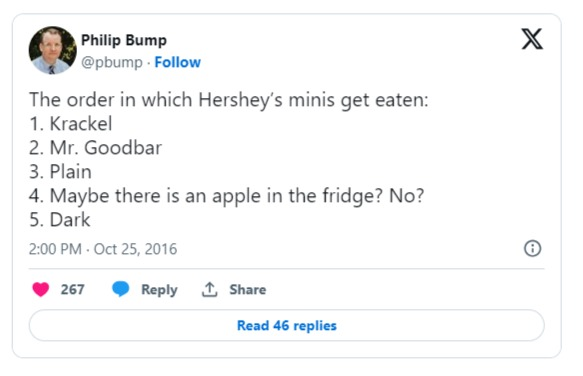

What these assessments haven’t fully accounted for, though, is the most fundamental division of all. Lurking at the heart of the Candy Controversies is the matter of milk chocolate versus dark chocolate, which is also to say Good Chocolate versus Bad Chocolate. Take this mini-ranking, from the Washington Post’s Philip Bump, which garnered approximately 5,000 replies, ranging from enthusiastic agreement to hot-fire objection, and started a small war of choco-partisanship:

So let’s settle it, once and for all—with the truth. Here, listed in no particular order, is definitive evidence that Milk Chocolate Is Superior to Dark Chocolate and If You Do Not Agree You Are Wrong Both Factually and Morally The End:

1. Milk Chocolate Tastes Good

I mean. I mean. This isn’t even a debate, right? Let’s move on.

2. Dark Chocolate Tastes Bad

Do you enjoy being reminded that the treat (“treat”) you are eating has been extruded from a crushed-up plant? Do you prefer desserts that go out of their way to inform you that they have been composed of beans? Then by all means, enjoy your Milky Way Midnight or whatever it is, but we really have nothing left to say to each other, because dark chocolate is bitter and aggressive, and, in general, I prefer my guilty-pleasure indulgences when they do not systematically attack me in the mouth. Also, dark chocolate is chalky. It doesn’t melt so much as it, for the most part, crumbles.

But I realize I am not an authority on this. So here is About.com—yes, the site so comprehensive in its knowledge of the world that only a preposition would do for its title—and its definitive Candy Glossary, which, it turns out, has already made the case for me (emphasis mine):

Dark chocolate is chocolate without milk solids added. Dark chocolate has a more pronounced chocolate taste than milk chocolate, because it does not contain milk solids to compete with the chocolate taste. However, the lack of milk additives also means that dark chocolate is more prone to a dry, chalky texture and a bitter aftertaste.

Right? Objective! And if you’re still not convinced, here is an actual academic paper that I did not purchase from Elsevier but whose abstract I definitely skimmed. It is titled “Sensory description of dark chocolates by consumers,” and its authors scientifically tested regular people’s assessments of the texture of dark chocolate. It concluded, scientifically:

With respect to mouthfeel, chocolate with a lower cocoa content was characterized as melting and creamy, whereas the product with the highest cocoa content was characterized as dry, mealy, and sticky.

Boom. Scienced.

3. Dark Chocolate Tastes Bad Specifically Because It Is Bitter

But, okay, to be fair, some chalky things are tolerable, right? Smarties, for one (see above). But, as About.com suggested, it’s the bitterness that really does dark chocolate in, since even the sweetest versions of the stuff are, in some way, sour. Those Special Dark bars they put in the Hershey’s Minis bags to offset the Krackels (they’re the worst of the milk chocolate options, Philip, I’m sorry) and/or make the whole selection seem a little fancier? If “special” means “bitter in flavor but also bitter because you could be having a Mr. Goodbar instead,” then yes, these bars are extremely special.

4. Dark Chocolate Is Snobby

I assume a) that there is a chocolate lobby, and b) that it has been working for many years to brand the more cacao-heavy versions of its products as luxury items. Just like DeBeers did with diamonds, Big Chocolate has seen to it that, while milk chocolate is accessible and ubiquitous, dark chocolate remains mysterious and exclusive. (See: the Ghirardelli Dark Chocolate Intense Dark Midnight Reverie® bar and its 86 Percent Cacao. Can’t argue with reveries!) And the branding, to be fair, has gone extremely well: Dark chocolate now has an image to maintain. Dark chocolate reads The Economist, and regularly quotes Bagehot to make all that reading worthwhile. Dark chocolate was totally into the restaurant before it was cool. Dark chocolate stopped liking the restaurant once it got cool. Dark chocolate hasn’t had a glass of Merlot since it saw Sideways. But dark chocolate is thirsty, so thirsty (and only partly because its mouth is full of mealy, chalky bean-chunks).

4.5. Milk Chocolate Is Basic, and That’s Totally Fine and Quite Possibly Pretty Great

Do you enjoy a Pumpkin Spice Latte every now and then, and do you sometimes even refer to this beverage, simply for brevity’s sake, as a PSL, and do you generally not feel that either of these things should be treated as evidence of your moral turpitude? Would you sometimes prefer McDonald’s french fries dipped in barbecue sauce to some hand-cut pommes frites served with a thimble of aioli?

I agree. If you’d like, I have this amazingly delicious Hershey’s bar that I’d be happy to share with you.

5. Dark Chocolate Is a Marxist Nightmare

Dark chocolate celebrates, in the most literal way possible, conspicuous consumption. Which, fine, is Veblen and not Marx, but they’re related, and anyway, something something bourgeois something something “responsibly sourced” and just see point 4 again, I don’t know. Dark chocolate is bitter and gross, I can’t believe we’re still having this discussion.

6. Dark Chocolate Is a Lie

Oh! Right! Remember the Mast Brothers? The bearded hipsters who got famous selling fancy chocolate bars under the evil-genius, farm-to-table-y premise of “bean to bar”? The ones who, allegedly, just took regular old chocolate and put it in pretty paper and charged $10 a chunk and basically made a mockery out of everyone who has ever loved chocolate, which is very, very many people?

And remember when Hershey funded studies that suggested the health benefits of dark chocolate, and when Mars placed its chocolate products in health-food aisles at Walmart and Target, to give the impression that they were “nutrition bars,” because Big Chocolate really is everywhere?

7. But At Least Dark Chocolate Is Not White Chocolate

White chocolate, to be clear, isn’t even chocolate. It is a product of chocolate’s aftermath: It is composed largely of cocoa butter—vegetable fat—that has basically been remaindered from the Vaseline lotion factory and then mixed with a sweetening agent and then squirted into foil and sold at a markup under the guise of confectionary indulgence, probably also under the direction of Big Chocolate.

So. Whatever your individual taste, whatever your random preference, whatever the complicated interplay of nature and nurture has led you to believe about what you happen to enjoy, candy-wise, this is the truth, and I will accept no other views. Except there is one tiny point, I’ll concede, that dark chocolate and its dark arts have going for them. White “chocolate” is proof that there is one thing worse than being bitter, mealy, untrustworthy snob-chocolate: not being chocolate at all.

* I also actively love Kraft Macaroni and Cheese, though, so basically take everything, when it comes to your correspondent’s culinary taste, with a grain of definitely-not-Himalayan salt.

Megan Garber is a staff writer at The Atlantic.

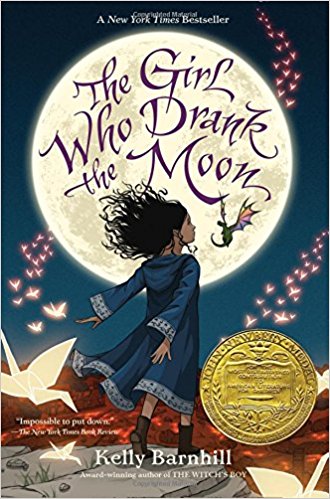

Kelly is an author, teacher and mom. She wrote THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, THE WITCH’S BOY, IRON HEARTED VIOLET, THE MOSTLY TRUE STORY OF JACK and many, many short stories. She won the World Fantasy Award for her novella, THE UNLICENSED MAGICIAN, a Parents Choice Gold Award for IRON HEARTED VIOLET, the Charlotte Huck Honor for THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, and has been a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, the Andre Norton award and the PEN/USA literary prize. She was also a McKnight Artist’s Fellowship recipient in Children’s Literature.

Kelly is an author, teacher and mom. She wrote THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, THE WITCH’S BOY, IRON HEARTED VIOLET, THE MOSTLY TRUE STORY OF JACK and many, many short stories. She won the World Fantasy Award for her novella, THE UNLICENSED MAGICIAN, a Parents Choice Gold Award for IRON HEARTED VIOLET, the Charlotte Huck Honor for THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, and has been a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, the Andre Norton award and the PEN/USA literary prize. She was also a McKnight Artist’s Fellowship recipient in Children’s Literature.